Media criticism is something I want to do more of. And now that I'm taking a journalism class, I can use my blog posts to double as homework in a stunning violation of ethics.

Our media is often guilty of pure stenography. Rather than providing readers with relevant facts or background information our "journalists" perform jobs that will soon be relegated to robots, writing as though they were transcribing videotape. And when then do stray from a rote just-the-immediate-facts approach it is more often to inject inanity and personal bias than to inform the reader.

The McClatchy take on Bush's UN address: "Bush astounds activists, supports human rights"

Speaking before the United Nations General Assembly, the president called for renewed efforts to enforce the U.N.'s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a striking point of emphasis for a leader who's widely accused of violating human rights in waging war against terrorism.

Now the New York Times coverage of the same: "Bush, at U.N., Announces Stricter Burmese Sanctions"

Mr. Bush referred repeatedly to the declaration, citing its first article, “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” as well as the 23rd, 25th and 26th articles, which call for access to employment, health care and education.

The declaration, a nonbinding resolution that was negotiated in 1948, calls on countries to protect a wide array of rights, including freedom of speech, assembly and religion, while prohibiting slavery, torture and arbitrary detention.

McClatchy chose to compare what Bush said to his previous actions, while the NYT played the part of credulous observer bereft of independent thought. Perhaps that is merely a difference in journalistic styles, or then again, perhaps not:

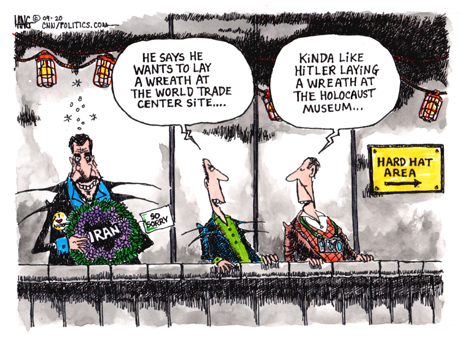

He said that there were no homosexuals in Iran — not one — and that the Nazi slaughter of six million Jews should not be treated as fact, but theory, and therefore open to debate and more research.

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the president of Iran, aired those and other bewildering thoughts in a two-hour verbal contest at Columbia University yesterday, providing some ammunition to people who said there was no point in inviting him to speak. Yet his appearance also offered evidence of why he is widely admired in the developing world for his defiance toward Western, especially American, power.

These are the first two paragraphs of the Times' coverage of Ahmadinejad's visit to Columbia University. Here the Times abandons the blank recitation approach, instead injecting the opinions of the piece writer. Later Ahmadinejad is accused of a "dodge" (rather than a "response") and his visit to New York is described as "dramatic theater".

Let's directly compare the Time's coverage of Bush and Ahmadinejad speaking to the UN:

Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the president of Iran, said Tuesday that he considered the dispute over his country’s nuclear program “closed” and that Iran would disregard the resolutions of the Security Council, which he said was dominated by “arrogant powers.”

In a rambling and defiant 40-minute speech to the opening session of the General Assembly, he said Iran would from now on consider the nuclear issue not a “political” one for the Security Council, but a “technical” one to be decided by the International Atomic Energy Agency, the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog.

Once again the Time's piece contains an immediate value judgement by the author, that his speech was "rambling" and "defiant." Note that Bush's speech was not described as "poorly enunciated" or "hypocritical."

These small darts of negative opinion are featured prominently in the Time's coverage of Ahmadinejad, immediately biasing the reader. Thank God the NYT has the "courage" to attack a man widely portrayed as the next Hitler while refusing to issue any judgements about our own country and President.

Had the Times described Bush's speech to the UN as "rambling", "nonsensical", "hypocritical" or "in willful disregard to his own conduct and policies" they would be taken to task, hoisted up as examples as what is wrong with our media. But describing Ahmadinejad as "rambling", "bewildering", "defiant" (as opposed to, say, "brave") and claiming that his remarks provided "ammunition to people who said there was no point in inviting him to speak"? That of course is perfectly acceptable because it exactly parrots the views of Washington insiders and our administration.

Surely Steven Lee Myers, who wrote covering Bush's speech to the UN, is aware of our own human-rights violations. When he wrote that Bush cited the "Universal Declaration of Human Rights" it must have occurred to him that the US may itself be violating it. (We violate numerous articles) He cannot be unaware that, as he reports of Bush's complaints with arbitrary detention, that arbitrary detention is a US policy Bush champions.

Journalists who cover specific topics for a living have a much broader understanding of them than casual readers and have a responsibility to convey that knowledge through their writing. Refusing to provide context or address obvious questions is an abdication of that responsibility. Reporting what people say while ignoring their actions, actions the journalists themselves are well-aware of, is a service only to those who speak loudest and most often.

According to the NYT that Bush spoke in favor of human rights is news; that he didn't mean it, which is not merely a matter of opinion but is evidenced by his own words and actions, is not.

Here is how the Time's reported Ahmadinejad's complaints against the US:

Without mentioning the United States by name, Mr. Ahmadinejad used his speech to carry out a full-scale assault on the country as power-mad and godless. He said its leaders “openly abandon morality” and act with “lewdness, selfishness, enmity and imposition in place of justice, love, affection and honesty.”

“Certain powers,” he said in a thinly veiled reference to Washington, were “setting up secret prisons, abducting persons, trials and secret punishments without any regard to due process, extensive tapping of telephone conversations, intercepting private mail.”

Note again the immediately biasing language, that Ahmadinejad launched a "full scale assault" (a word conveying violence) on the US, calling us "power-mad and godless" -- which is not an actual quote from Ahmadinejad. Let's re-write the above in a way that is unbiased, factually accurate and informative:

Without mentioning the United States by name, Mr. Ahmadinejad used his speech to carry out an accurate attack on the US' numerous human-rights abuses.

“Certain powers,” he said in a thinly veiled reference to Washington, were “setting up secret prisons, abducting persons, trials and secret punishments without any regard to due process, extensive tapping of telephone conversations, intercepting private mail.”

Ahmadinejad said the US runs secret prisons and abducts people, but he didn't merely say it -- the NYT has confirmed it with its own investigations. The original NYT version gives the reader no way to evaluate the veracity of the statements when the NYT knows full well that the statements are accurate.

Read more!